What colour were the first Corpus pelicans?

Consultant Archivist Dr Lucy Hughes and Book Conservator Mito Matsumaru turn to science to research the College's original ‘Grant of Arms’.

All Corpuscles know the iconic coat of arms of Corpus Christi College, which features a combination of heraldic pelicans and lilies. We see it on buildings, backpacks, official letters and more recently facemasks. But where do the pelicans and lilies on a blue-and-red background come from?

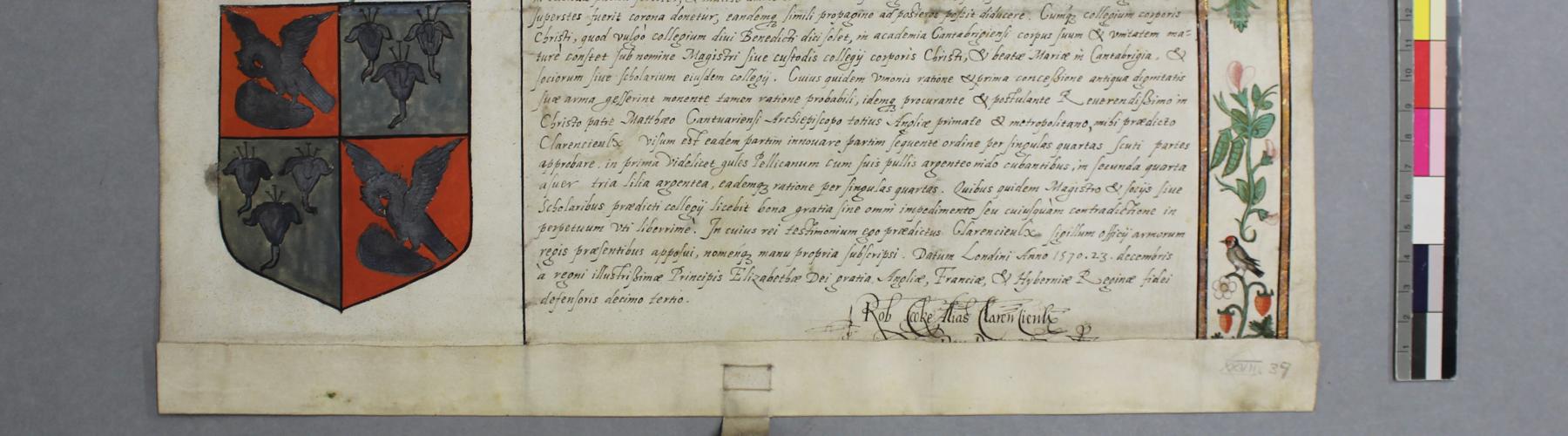

The symbols date back to the College's founding. In heraldic terms, the College’s arms are "Quarterly 1st and 4th Gules a pelican in her piety argent 2nd and 3rd Azure three lilies slipped 2 and 1 argent". The arms were granted in 1570 by Robert Cooke (d1593), Clarenceux King of Arms, at the behest and expense of Matthew Parker, Archbishop of Canterbury and former Master of Corpus. The two elements symbolise the founding Guilds of Corpus Christi and the Blessed Virgin Mary.

The ‘Grant of Arms’ of Corpus Christi College officialised this coat of arms around 450 years ago. The original parchment document has been carefully preserved by the College since its issuance in 1570. Recently, the Cambridge Colleges Conservation Consortium, hosted at Corpus Christi, was tasked with analysing the condition of this document and — if necessary — to take appropriate conservation measures to maintain the Grant's condition.

Book Conservator Mito Matsumaru said, "While the document is still in a very good overall state, we immediately noticed that the colourants on the Coat of Arm showed signs of a strong discolouration process, with many areas showing a range of dark dull grey tones."

A close-up view of the of the Coat of Arms shows discoloration of the original pigments.

A close-up view of the of the Coat of Arms shows discoloration of the original pigments.

Discolouration is a common issue with older documents as colourants over the centuries undergo a range of slow chemical transformations. This can be triggered by exposure to light, humidity or simply air. Unfortunately, because many colourants discolour towards similar tones the original colours can't be directly identified.

But there were some clues to be found in the text of the manuscript itself, where the coat of arms is described in medieval Latin:

Visum est eadem partim innouare partim sequente ordine per singulas quartas scuti partes approbare, in prima videlicet gules Pellicanum cum suis pullis argenteo nido cubantibus, in secunda quarta asuer tria lilia argentea, eademque ratione per singulas quartas.

The text indicates that silver is to be used for the lilies and pelicans (argenteo/a) and that red (gules) and blue (asuer) were selected for the background of the coat of arms. However, this information did not specify the nature and exact shade of the original colourants as both the blue and silver have discoloured to grey.

This is where science came to the conservators' aid. In 2019 a non-destructive pigments analysis of the colours was conducted by the Fitzwilliam Museum. This allowed the researchers to establish the material used in the original colourants:

- The red areas used vermillion, made from the powdered mineral cinnabar

- The blue areas used smalt, a potassium glass containing cobalt

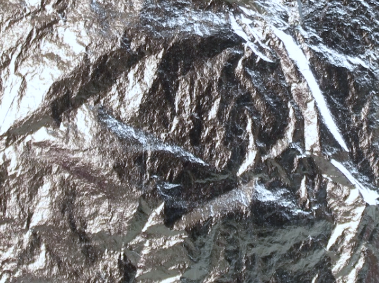

- The silver areas used silver leaf

These findings indicate that the original coat of arms had very bright, vivid colours with a strong metallic sheen provided by the silver leaf. Silver leaf and smalt are well known to heavily discolour to grey, which is certainly evident in the present state of the coat of arms.

|

|

Left: Red (cinnabar), Blue (light/dark smalt colours). Right: Silver (silver leaf). All purchased from L. Cornelissen & Son.

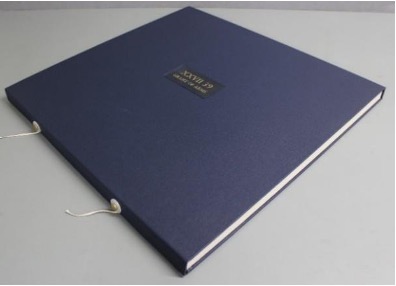

To prevent further damage to the object, a bespoke storage enclosure was designed to limit environmental exposure.

|

Bespoke storage enclosure, inside and outside.

This work demonstrates the synergy of historical, bibliographical and scientific approaches to understand the materiality of historical documents, and help to guide their conservation.

A full article about the analysis is now under peer review and is expected to be published in 2022.

The authors wish to show their gratitude to Dr Paola Ricciardi (Fitzwilliam Museum) for enabling us to carry out this research. Also we would like to thank Miss Mila Crippa (Fitzwilliam Museum); and Dr Stefano Legnaioli (ICCOM‐CNR, Pisa) for their support for analysis in 2019.

To find our more about the work of the Cambridge Colleges' Conservation Consortium, please see their webpages.