Thinking about Thais

As the Parker Library Early-Career Research Fellow this year, I’ve had the privilege to spend an extended period of time working with one manuscript: CCCC MS 385, a book made up of four different medieval volumes. I got interested in this book only in passing and in relation to a very small part of it: one seventy-word passage close to the end, re-telling the ancient story of the ‘harlot saint’ Thais, who is the focus of my larger research project. But getting a picture of the manuscript as a whole has become more complex and more interesting the closer I’ve looked.

|

|

|

|

|

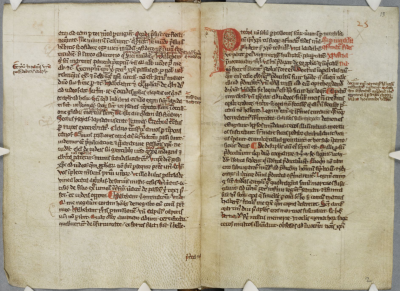

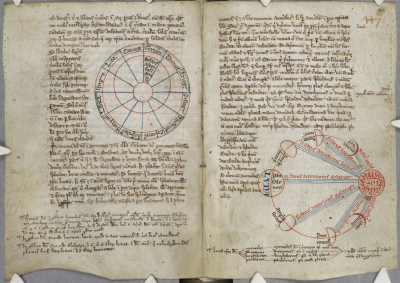

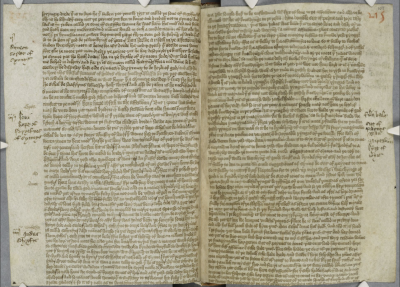

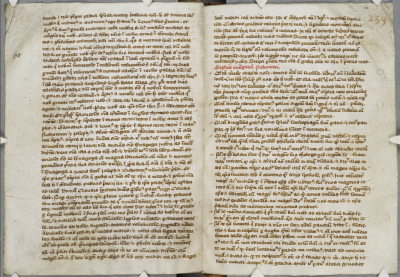

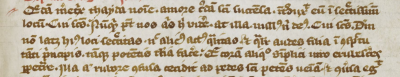

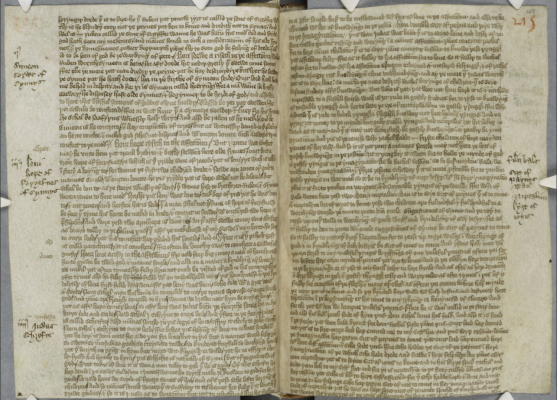

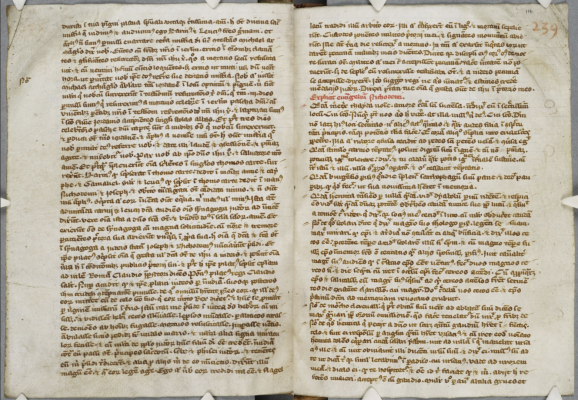

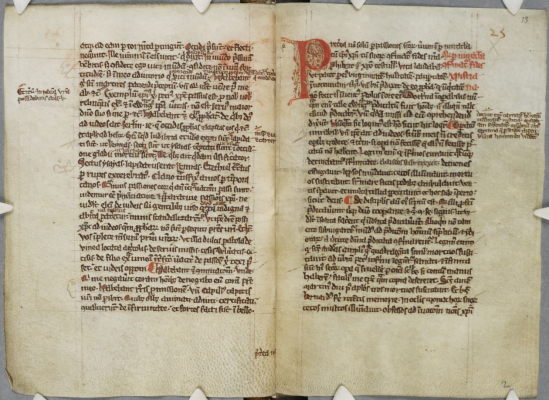

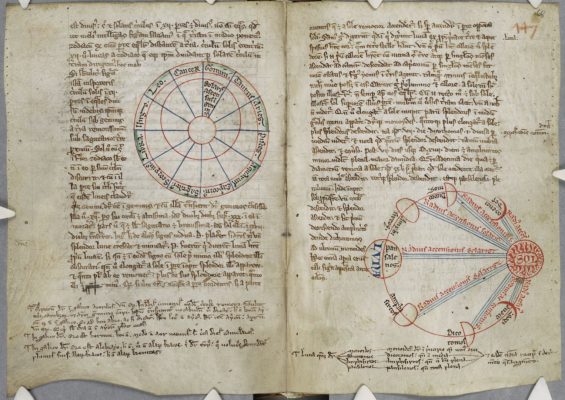

Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, MS 385, pp. 24-25, 146-47, 214-15, 238-39 (sample pages of the four different volumes).

Medieval manuscripts are often used in scholarship principally for what they contain—historical records, literary works, images and so on. But one major trend in recent medievalist research is to emphasise the ‘whole book’, or the full context of any given text or other item. These cultural phenomena don’t simply appear by themselves, in the carefully tidied and curated form of modern editions: they came down to us by means of physical books, written by hand on treated animal skin, scribbled on and damaged, used by different people for different purposes at different times. All those aspects can affect how we understand the written content of a book.

And it wasn't the norm for medieval books to contain one single text, or even one genre of text. Very often, texts that seem very different to one another to modern eyes will keep close company, without any obvious reason why the writer or reader might want them together. So when we think about an individual text in its manuscript context, we have to decide whether to look for those kinds of reasons - why different texts work together or how they speak to each other, whether the combinations and juxtapositions are intentional or otherwise.

Thais the harlot keeps strange company

When I first got interested in CCCC MS 385, it was because of one text among many. As a postdoc I am researching the story of Thais—an early Christian narrative about a sex worker who became a saint.

Thais looking out from her enclosure. Paris, Biblothèque nationale de France, MS Esp. 44 f. 219v detail. Public domain. Source gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France.

An account of her dramatic conversion turns up in CCCC MS 385 as the first of a sequence of ‘exempla’: short edifying stories, often surprising or memorable, generally the sort of material used in sermons or moral treatises to illustrate points and maintain an audience's attention.

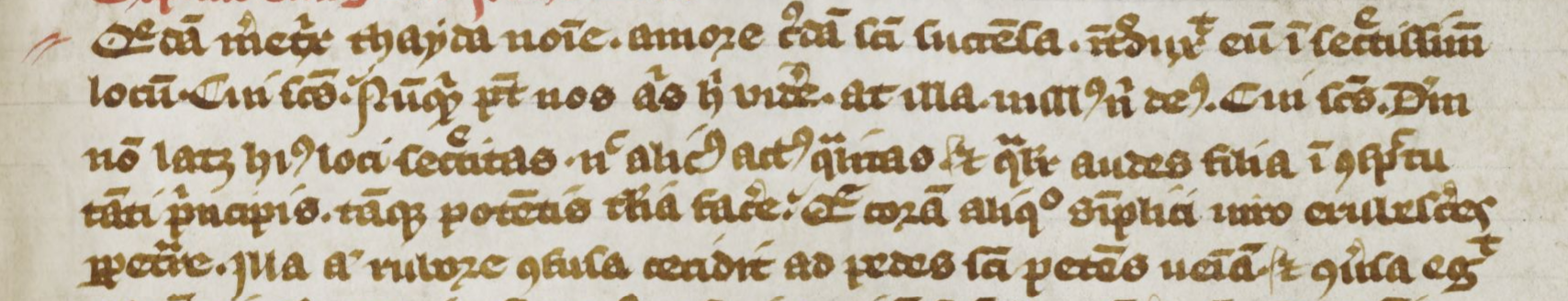

In this version of the story, the harlot Thais is overcome with desire for a particular ‘old man’ (a term for one of the ‘Desert Fathers’, the first monks who fled to the North African deserts in the early centuries of Christianity). She meets him in a private place but is disarmed by his challenging question: if you know that God can see all, why do you do such shameful things even in private? Thais is overcome with shame, repents at the monk’s feet, and is converted.

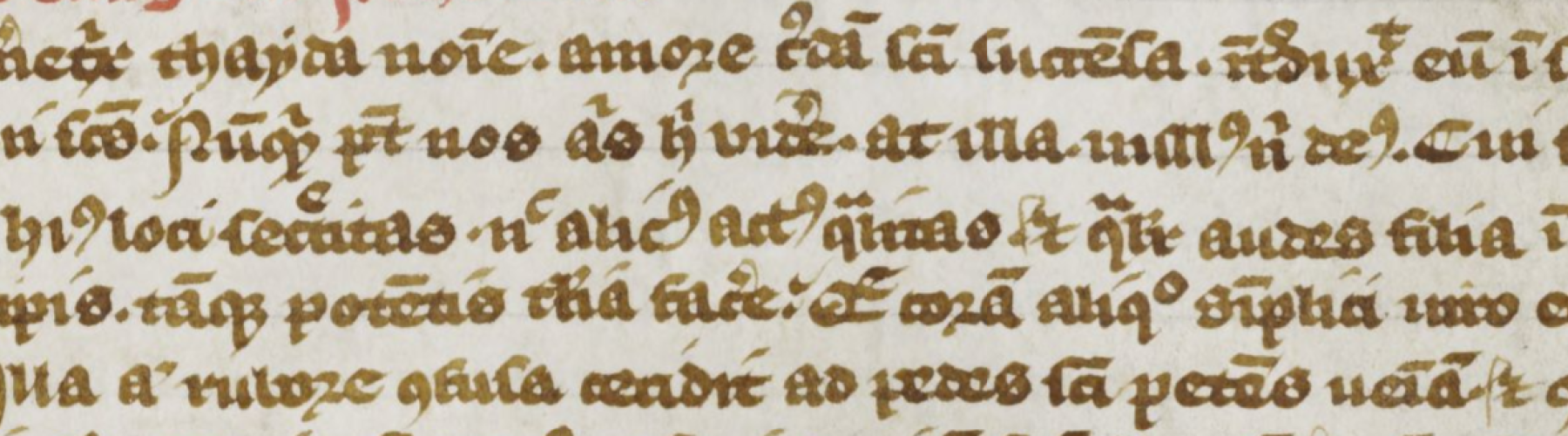

‘A certain harlot, Thais by name, burning with love for a holy man, led him into a private place…’ (CCCC MS 385, p. 239)

Now have a look at some of the stories which follow after this one—copied by the same neat hand in one unbroken block:

- A man undergoing temptation puts his finger into a candle flame, to remind himself of the pains of hell which come from giving in to temptation.

- A Parisian citizen buys a coffin and fills it with bread for the poor.

- A hermit sees a devil laughing at another devil, which was riding on a woman’s hem and fell off it into the mud.

- A dead monk appears to his abbot and complains that his brothers aren’t praying for him as much as he used to pray for them.

- A hermit is disappointed to be told he is on the same level of holiness as a bearkeeper; he goes to see the bearkeeper (and the bear), who sends him to his wife. A strange series of events unfolds as she shows him the strategies they use to combat temptation—eating bread made from ash, among guests eating fine food; sleeping in a rich bed lined with hair-shirt material; immersing him in icy water. The hermit lives a stricter life thereafter.

These are just a few of the early stories in the sequence. There are 38 in total, featuring dukes, scholars, kings, and usurers; two stories about people forced to ride demonic horses and three about revenants from the dead; monkeys, birds, a priest struck by lightning, and an invisible pig.

So how does Thais fit into this panoply of anecdotes, parables, and shaggy dog stories? I initially approached the ‘harlot saint’ story as a literary scholar—working with the full-length accounts of Thais as literary works, tracing how they present the characters and the narrative arc, examining the various different techniques used to present this complicated story of notorious sinner turned religious recluse.

But CCCC MS 385 doesn’t let me do that. For one thing, it only contains half the Thais story as we find it elsewhere, cutting out the ‘saint’ half of her life. It also simplifies the character drama, not naming the converting monk (elsewhere known to be Paphnutius), and gives Thais the conventional harlot’s motivation of lust to initiate their meeting, a detail not found anywhere else—Thais is usually presented as more greedy than lustful, driven by profit rather than desire.

Thais kneeling in front of Paphnutius. Paris, Biblothèque nationale de France, MS Fr. 242, f. 231v detail. Public domain. Source gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Connecting the dots

So we’re forced to look more widely and think about the context of this little text. You can make thematic connections between Thais and some of the other exempla: there is another story about a woman inflamed with lust who is rebuked by the man she desires, for example, and another story about a harlot saint, Mary Magdalene. We have several stories about Desert Fathers and several about conversion. Temptation and shame are significant themes across many of the stories.

But this kind of connecting the dots, too, is complicated. The stories don’t follow an obvious thematic order, nor are they labelled for reference in a way that might suggest they were used by a preacher looking for material on particular topics. The majority of them actually come from a reference work which does have that sort of user-friendly cross-referencing structure, Arnoldus of Liège’s (active c. 1265–1307) Alphabet of narratives (Alphabetum narrationum), but in CCCC MS 385 the scribe has copied in several chunks from that alphabetised work without the accompanying apparatus. And the first nine stories, including Thais, don’t come from that collection at all. They seem to be randomly strung together, potentially retold from the scribe’s memory.

Are we seeing a ‘best of’? A thematic sequence not currently clear to me? A pragmatic attempt to fill in blank pages after the longer text which begins the booklet (the apocryphal Gospel of Nicodemus)? It’s difficult to know, and my research this year is continuing to explore this issue. Thais was a complicated figure in medieval culture: the saint’s life co-existed with the use of the name as a stock term for a profit-minded prostitute, a usage dating back to the pre-Christian classical period but which continued as a significant (and under-studied) strand of the repertoire of medieval educational literature. So Thais lived in a strange place between her Christian and non-Christian lives, a duality which does seem to chime with the exuberant variety of the exempla in CCCC MS 385—but there are lots of questions still to answer.

Dr Alicia Smith