Healing the sick

Dr Philippa Hoskin, Gaylord and Dorothy Donnelley Fellow Librarian, shares fourteenth-century reflections on healing the sick.

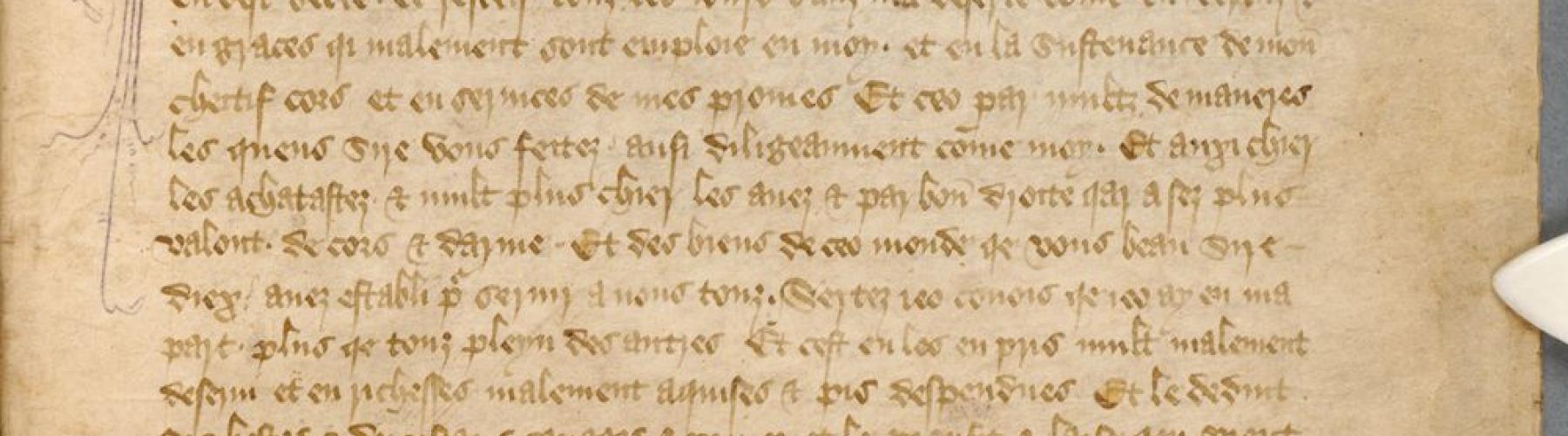

Parker manuscript 218 Le Livre de Seintes Medicines, a late fourteenth-century volume, is the earliest surviving Anglo-Norman treatise known to have been written by a layman. That layman was Henry first duke of Lancaster (c.1310 – 23 March 1361) who applied to Edward III, on behalf of the guilds of Mary the Virginand Corpus Christi, for permission to found the new college.

It is a devotional text in which sickness of the body is compared to sickness of the soul: Christ, as doctor, heals the senses from infection. When Henry wrote this work in 1354, plague was a familiar visitor to England (in fact, Henry died of plague himself in 1361). Not surprisingly, then, his descriptions of physical sickness reflect experience of the disease. We learn that goat’s milk drunk in May was considered efficacious, on the grounds that the vegetation eaten by goats in May had absorbed the goodness of the sun, which could be passed on to the sick. Warm rose water was used to refresh those with fevers (although, presumably only those who were rich, like Henry) and, if a fever got worse, the still bleeding body of a freshly-killed cock might be placed on a patient’s head.

In particular, Henry describes the use of ‘triacle’ – a medicine made of poison, used to drive out the other poison of infection.

‘If a man is poisoned, he has to get some medicine or else he is doomed to die quickly. And nothing is so good for him as triacle. This triacle is made and tempered with the strongest venom one can find anywhere. And, if it is stronger than the venom within the man, it expels that venom through its strength and virtue, and so the man is cured and does not die. But if the venom in the man is particularly potent and pernicious and has lingered in him for a long time, then the triacle cannot help and the man is made worse by it. For if one venom cannot expel the other, they will unite to destroy and kill the man.’

Henry tells us that this perilous medicine is made by smothering a scorpion so it disgorges its venom. In fact, we know from other sources, that it was usually made from the mashed flesh of snakes – rather cheaper and easier to obtain than scorpion venom.

This process, he says, is like the war between good and evil fighting with each other in the human soul. Triacle is like the traps of the devil. These temptations can have a good result for the sick soul if they make a person turn to God for help. On the other hand, if the temptations are strong and spiritual sickness has gone untreated for too long, they may lead to the destruction of the soul.

There was always a tendency in the medieval mind to try and find direct, causal links between natural occurrences, particularly those that caused human suffering and death, and internal spiritual states. Earthquakes, floods, droughts and plague were commonly explained as a result of human sin. In Henry’s treatise we can see how a devout individual was able to transform his own experience of physical illness and contemporary medicine into a powerful allegory about the health and wellbeing of people’s souls.

Images: CCCC ms 218, f. 1v. The opening of Le Livre de Seintes Medicines