Art, Astrolabes, and Medieval Manuscripts

The Parker Library is privileged to host an exhibition that combines medieval manuscripts with astrolabes (thank you Whipple Museum for the loans!) and modern art works. Our second Parker Library Early-Career Research Fellow, E.K. Myerson has curated the latest exhibition: Anchorless Bodies: Navigating Arabic in Medieval Manuscripts with works by Emii Alrai. The display will remain in the Wilkins room cases from 25 May until 25 September 2023.

Tours of the exhibition can be booked through our Eventbrite page. However, if you cannot make it (or even if you can!), here’s a digital tour of the exhibition.

Parker Library Early-Career Research Fellow, E.K. Myerson (right) with visitors, on the opening day of the exhibition. Image by Fiona Gilsenan.

Emii Alrai uses the phrase ‘Anchorless Bodies’ to describe her artworks: sculptures and drawings inspired by archaeological excavations, medieval astronomy, and ancient industrial practices. The exhibition showcases a range of medieval journeys: imaginative and physical travel. Maps and notebooks contain records of voyages to crusader and colonial settlements. The cases preserve books which could not have been written without translators moving between places, bringing their libraries with them – from Tunisia to Italy, from Jerusalem, Baghdad, and Al-Andalus to England. People have always arrived at this island on boats.

Arriving in medieval England, Arabic books and instruments were used as tools for navigation. As most English readers could not understand Arabic, these objects also required aids for navigation – like translations and illustrations.

Travel

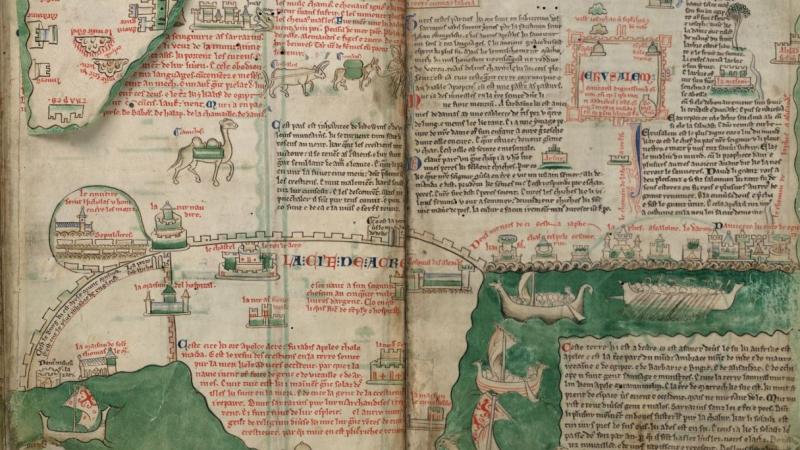

The exhibition opens with Matthew Paris’s autograph copy of his map of the route to Jerusalem, present in his Chronica Maiora. The map was drawn during the period of the Christian crusader settlements in Greater Syria. The manuscript invites a contemplative encounter with the Holy Land. To see the full map, you would need to open out the flap – using your body to aid the experience of imaginative travel.

Matthew Paris, Chronica Maiora (now CCCC MS 26, fol. iii verso-iv recto; c. 1240-55)

Close by stands Emii Alrai’s Ceramic Vessel (2023). Despite it being just recently made, the vessel echoes the form and texture of an excavated artefact. It might as well have been brought to England from the crusader settlements, as shown in Matthew Paris’s map.

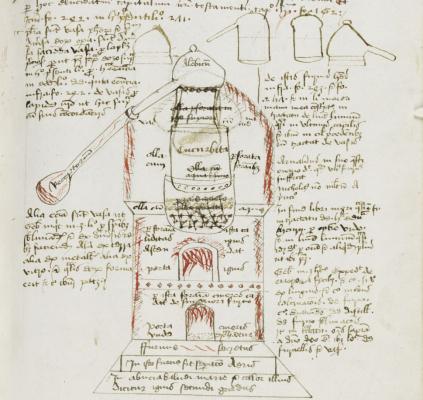

Alchemy

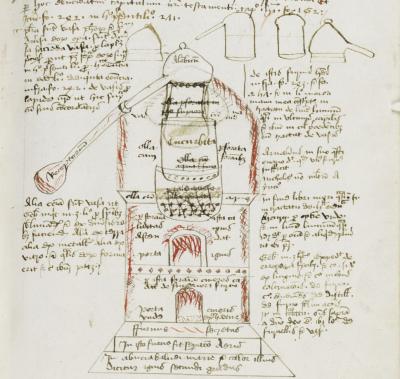

In a copy of Ramón Lull’s Alchemical Works the vapour travels up and around the glass vessels arranged over this flaming furnace. The diagram is labelled with Latin terms for alchemical instruments, borrowed from Arabic – the ‘alembic’, a distillation vessel, sits at the top. The image is paired with Emii Alrai’s untitled drawing of a vessel (2023) that looks like it could have been used in the alchemical furnace. Ceramic fragments are arranged over its surface, like debris.

Ramon Lull’s Alchemical Works (now CCCC MS 112, p. 37; late 15th–early 16th century)

Astrolabes

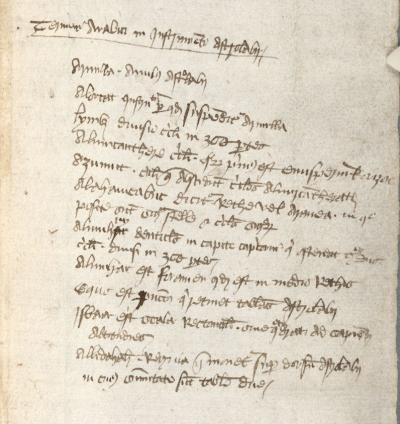

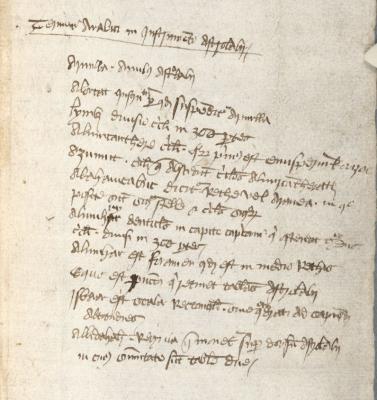

A practical tool to help on one’s journey, the astrolabe was developed in the Islamic world. They were essential for navigation both on land and at sea. In the 15th century an Englishman William Worcester attempted writing down ‘Arabic Terms for the Instrument of the Astrolabe’ – Alorcat, Almucanthere, Azumut, Alahamcabuc, Almuhry, Almuhar, Albidahalj …

William Worcester, Itineraries (now CCCC MS 210, p. 261)

Beside William Worcester’s notebook is a real astrolabe made by Ahmad b. Umar Al-Jilani, signed in Kufic script.

Astrolabes on loan from the Whipple Museum of the History of Science (Wh. 1263, 15th century and Wh. 2354). Images courtesy of the Whipple Museum.

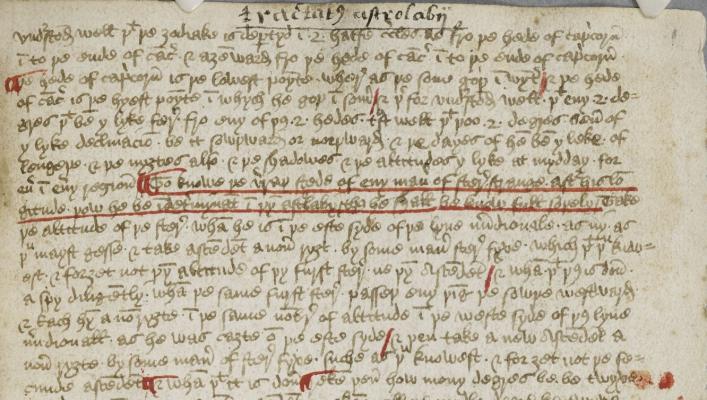

Geoffrey Chaucer (d. 1400) is best known as a poet, but he also wrote scientific prose: the Treatise on the Astrolabe. Addressing the text to his son, Lewis, Chaucer promises that his English instructions will as good ‘as the noble Greek scholars find them in Greek, and the Arabs in Arabic, and the Jews in Hebrew, and the Latin folk in Latin’. Next to Chaucer’s Treatise is a 15th-century brass astrolabe (Wh. 1263), likely made in Italy, imitating Islamic designs.

Geoffrey Chaucer, Treatise on the Astrolabe (now CCCC MS 424, fol. 1r; late 15th century)

Astronomy

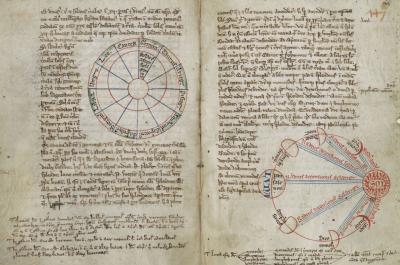

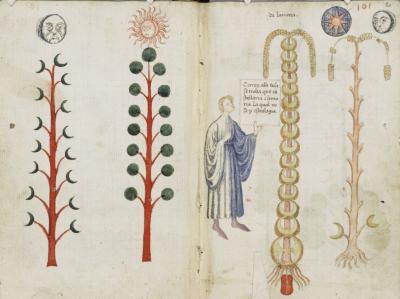

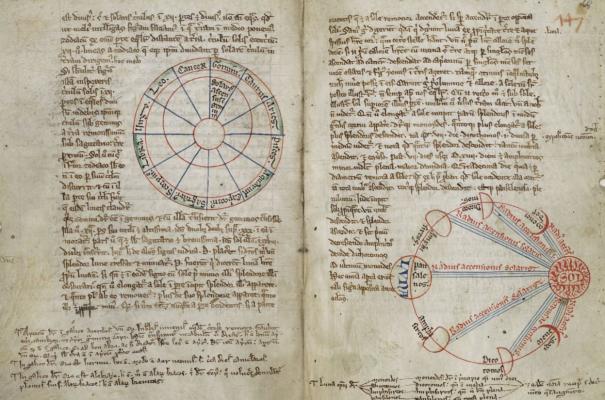

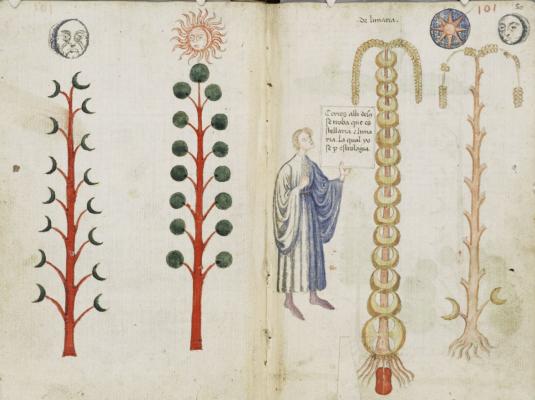

Look up at the stars. A mid-13th-century manuscript is paired with Emii Alrai’s Virgo (2022). The manuscript contains astronomical diagrams by Matthew Paris, the same artist who drew the map of Jerusalem in the Travel section above. Here he has drawn the Zodiac, and the phases of the moon.

[image 7]

Astronomical diagrams in William of Conches (c. 1080-1154), Dragmaticon (now CCCC MS 385, pp. 146-147; mid-13th century)

Stories and translations

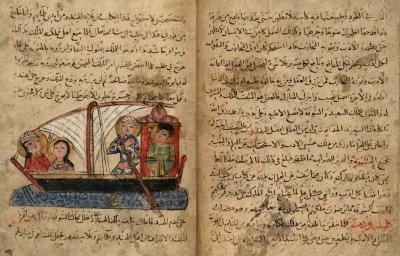

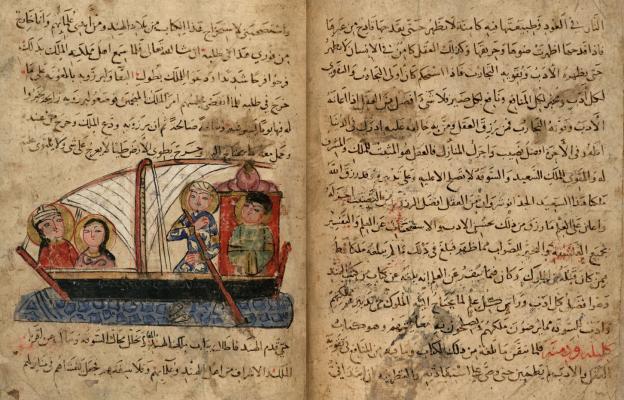

One of the exhibition cases contains some translated and converted texts. In a manuscript containing Kalīlah wa-Dimnah by Ibn al-Muqaffaʻ (d. c. 760) a series of moral fables are translated from Sanskrit and Persian into Arabic. This 14th-century copy did not arrive at the Parker Library until 1796, donated by Captain W.T. Sandiford, a translator of Persian for the East India Company.

Ibn al-Muqaffaʻ, Kalīlah wa-Dimnah (now CCCC MS 578, f. 6r; 14th century)

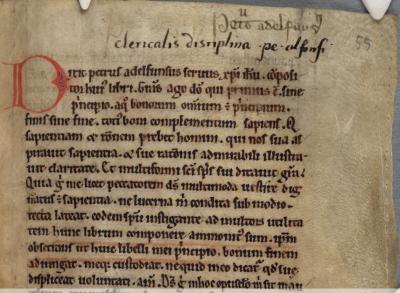

The case also contains two texts by Petrus Alfonsi (b. 1062–d. 1140). He was born Moishe Sephardi, speaking Arabic and Hebrew, in the Jewish community of Muslim-ruled Al-Andalus. Disciplina Clericalis is a selection of moral fables, based on Arabic literary traditions. This was the first storytelling collection of its kind to be written in England and was wildly popular. The second text, On the Conversion of Petrus Alfonsi (now CCCC MS 335, 15th century), is a narrative account of the translator’s conversion that became a tool of anti-Jewish propaganda.

Petrus Alfonsi, ‘Disciplina Clericalis’ (now CCCC MS 451, fol. 55r; 12th century)

Medicine

In another case the visitor will find a 13th-century unbound copy of a Latin medical treatise Viaticum by the Benedictine monk Constantine Africanus (d. before 1098/1099). Stained, decorated with portraits, and densely glossed in the margins, this is a book which was heavily used. The story is that when Constantine moved from Tunisia to Italy in the 11th century, he was so horrified by the lack of medical knowledge in Europe, that he immediately sailed back to Tunisia, returning with his personal library of Arabic books, which he then translated into Latin.

Constantine Africanus, Viaticum (now CCCC MS 511, fols. 38v-39r; 13th century).

A 15th-century work On the Virtues of Lunary rounds up the exhibition. The medical and alchemical uses of lunary can be traced back to the works of Maria Prophetissa (ca. 0-200 CE), a Jewish alchemist based in Hellenistic Egypt. The plant is seen in different stages of its life: crescent at night-time, round in the daytime, ready to be harvested, and after its moon-like leaves have been cut.

On the Virtues of Lunary (now CCCC MS 395, fols. 49v-50r; 15th century).

E.K. Myerson

Parker Library Early-Career Research Fellow

Follow us on Twitter @ParkerLibCCCC

The display has been arranged in collaboration with the Whipple Museum and is supported by AHRC IAA Funding.

Special Thanks: Philippa Hoskin, Tuija Ainonen, Joshua Nall, Genny Silvanus, Flavio Marzo, Roxanne Gherasim, and Emii Alrai.