What does Bede teach us about drawing lessons from the past?

Dr Philippa Hoskin, Gaylord and Dorothy Donnelley Fellow Librarian, reflects on what Bede has to teach us about drawing lessons from the past.

When the world seems to turn upside down, and old certainties evaporate, many people find themselves taking stock of the old, assessing what should usefully be kept, and making plans for a new and uncertain future. For a historian, this often prompts reflection about what is in danger of being lost or forgotten, and inspires them to draw meaningful bridges between the past and the present.

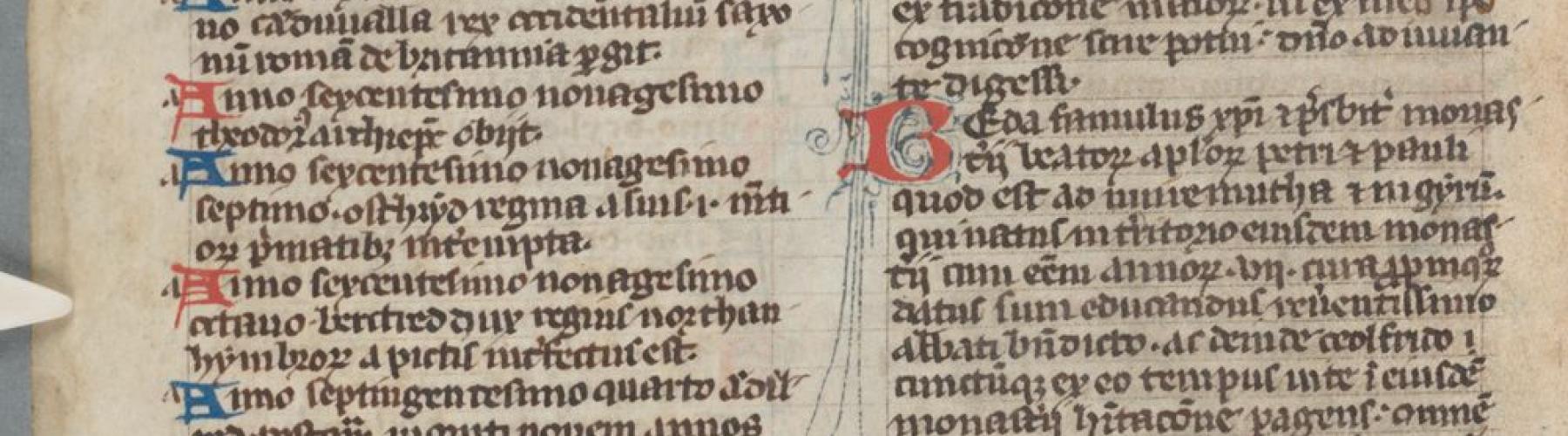

Bede (c.673–735 C.E.), sometimes known as the "Father of English History", was surely influenced in his work by the dramatic events of his childhood. Towards the end of his most famous work, the Ecclesiastical History of the English People, Bede provides the only information he ever gives his reader about himself: "Bede, the servant of God, and priest of the monastery of the blessed apostles, Peter and Paul, which is at Wearmouth and Jarrow; who being born in the territory of that same monastery, was given, at seven years of age, to be educated by the most reverend Abbot Benedict, and afterwards by Ceolfrith."

This connection with the abbot Ceolfrith provides us with a significant clue about Bede’s life and underlying motivation for his life’s work. In the life of Ceolfrith we’re told that in the great plague of 686 C.E. only Ceolfrith and his young pupil (long identified as Bede) went unharmed. They carried on the services together and as lone survivors they refounded the monasteries, maintaining the reassuring continuities of former times, but also going on to forge a new scholastic outlook.

Amongst Matthew Parker’s manuscripts at Corpus are three copies of Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People. One is an eleventh-century version in Old English, the translation made at King Alfred’s (848/849–899 C.E.) instruction, and the other two are fourteenth-century Latin versions. Interestingly, Parker himself found Bede’s work useful when he came to write his own version of the history of the English Church, one which attempted to cast the upheaval of the Protestant Reformation in England as less of a rupture or innovation and more of a returning to the old ways of doing things.

Evidence of Parker’s close engagement with these works is plain because we can still see where he marked up the text. One thing that particularly seems to have appealed to Parker is the discovery that Bede, like himself, supported his scholastic work by the collecting of books. In the medieval manuscript biography of Bede (MS 159 f. 69v) Parker has carefully underlined in his distinctive red pencil the phrase "Moreover, he gathered together a most famous library’.

Image: CCCC ms 159 f. 69v.