Misspellings, unfortunate additions and a case of mistaken identity: Matthew Parker’s Northumbrian Gospels.

The Parker Library is proud to be the single largest lender of manuscripts to the British Library’s magnificent exhibition, Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms: Art, Word, War. In a series of blog posts spanning the Christmas holiday and into the New Year, we will shine a spotlight on eight of the eleven Parker manuscripts currently on show, beginning with the magnificent Northumbrian Gospels, produced at the turn of the eighth century.

When you think of Anglo-Saxon Gospel books, there’s a good chance you’re imagining the richly illuminated pages of the Lindisfarne Gospels, full of zoomorphic interlace and bold pigment. Our manuscript is believed to be a sibling to this famous book, probably also a product of the Lindisfarne scriptorium at a similar date, and is certainly one of the oldest surviving decorated books in Britain. Multiple illuminated Gospels survive from the Anglo-Saxon period, and Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms brings many of the finest under the same roof for the very first time. This is particularly exciting for CCCC MS 197B, as the Parker manuscript is a fragment of what was once a much larger codex,and the exhibition reunites it with its other half, British Library, Cotton MS Otho C.V, previously owned by Sir Robert Cotton (d.1631). However, history has not been equally kind to both portions: the Cottonian fragment was badly damaged in the Ashburnham House fire of 1731, and viewing the two side by side provides a lesson in the felicity of manuscript transmission and survival in the post-medieval era.

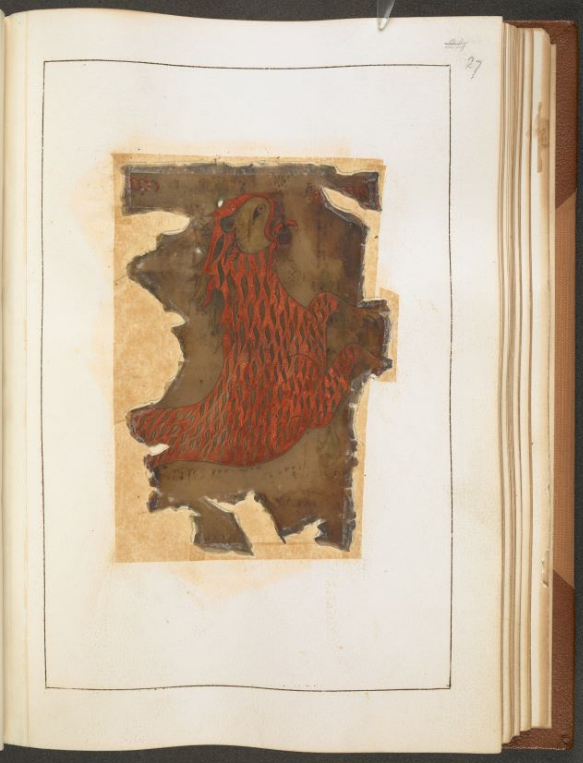

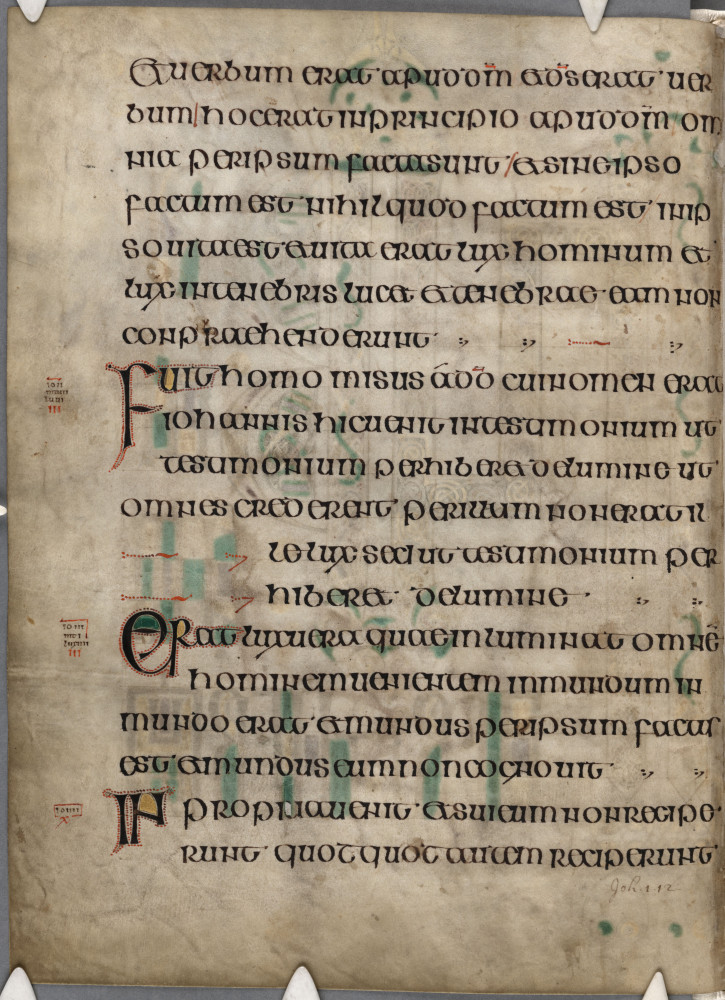

When complete, each Gospel text was presumably prefaced by an evangelist symbol and elaborate initial page, though in its current form only John’s eagle (imago aquilae) and incipit survive from the Parker portion of the manuscript, while the lion symbol of Mark (imago leonis) is visible in the Cottonian fragment, though badly burned (see image on the left). Still, the manuscript evinces the same kind of sumptuous calligraphic beauty we expect from books produced in the Insular tradition. The famous incipit to John – In principio erat verbum – is set out in elaborate format with a highly stylized In and p ornamented with boldly coloured interlaced foliage and geometric patterns, as well as spiral ornament in the finials and interlace birds in the doubled bowls of the p; a piece of art marred only by the infamous misspelling of the Latin verb erat as eret.

When complete, each Gospel text was presumably prefaced by an evangelist symbol and elaborate initial page, though in its current form only John’s eagle (imago aquilae) and incipit survive from the Parker portion of the manuscript, while the lion symbol of Mark (imago leonis) is visible in the Cottonian fragment, though badly burned (see image on the left). Still, the manuscript evinces the same kind of sumptuous calligraphic beauty we expect from books produced in the Insular tradition. The famous incipit to John – In principio erat verbum – is set out in elaborate format with a highly stylized In and p ornamented with boldly coloured interlaced foliage and geometric patterns, as well as spiral ornament in the finials and interlace birds in the doubled bowls of the p; a piece of art marred only by the infamous misspelling of the Latin verb erat as eret.

Today, the manuscript bears material witness both to Parker’s achievements as collector but also to his occasionally unfortunate practices as antiquarian. Despite his erroneous belief in the book’s august pedigree, Parker rebound his section with a number of miscellaneous fourteenth- and fifteenth-century works (now preserved in CCCC MS 197A), trimmed its leaves to fit the size of the volume’s other items,and reversed the order of Luke and John so that John’s majestic eagle formed a grand frontispiece (see image below).

The main text is written in a very fine and regular Insular half-uncial script, with frequent ornamentation: the beginning of each section contains a delightful initial with decorated finials, outlined in red dots,while the ends of sections are marked by sequences of dots and flourishes, also often in red. The text itself is the work of two scribes: John and Luke are composed in different hands, the latter being smaller, though both are expert,and their work magnificently written. An analysis of the script, particularly that of the Cottonian fragment, reveals several shared characteristics with the script of Eadfrith in the Lindisfarne Gospels (British Library, Cotton MS Nero D.IV), making an association with the Lindisfarne scriptorium all the more likely. However it has also been argued that the manuscript also contains another hand reminiscent of an Irish-trained member of the Echternach scriptorium, linking the manuscript with the Echternach Gospels (Paris, BnF, MS lat. 9389). To muddy the waters still further, certain features of the volume’s contents, principally its Gospel texts and canon tables, have drawn comparisons with the Durham Gospels (Durham Cathedral Library, MS A.II.17) and the Book of Kells (Trinity College, Dublin, MS 58), raising connections with the communities of Iona and Kells, Co. Meath respectively. Ultimately, whatever the truth of the manuscript’s origins may be, the Northumbrian Gospels undoubtedly belong to a glorious family of celebrated manuscripts of illustrious pedigree. Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms brings together almost every single member of this family – a truly magnificent assemblage – offering an extraordinarily rare chance to see them all, but even more marvelously, to view them in context, as part of the visual and palaeographical context of this glorious family reunion.

By a strange twist of fate, the Northumbrian Gospels owes its survival to centuries-old case of mistaken identity. Parker acquired his portion because he believed it had once belonged to St. Augustine of Canterbury (d. 604), being one of the books those books brought by the great man and his followers when they arrived in England in 597 AD, sent by Pope Gregory to convert the English to Christianity. This belief is inscribed at the top of its first page, where is written, in Parkerian hand: “fragmentum quatuor euangeliorum. Hic liber olim missus a gregorio pp. ad augustinum archiepiscopus: sed nuper sic mutilatus” (‘A fragment of the Four Gospels. This book was once sent by Pope Gregory to Archbishop Augustine: but lately so mutilated’).

Although Parker was mistaken, he was not alone in this belief, neither in his own time – after all, his Sir Robert Cotton acquired his portion of the manuscript for the same reason – or that of his forebears. Indeed the book’s mistaken provenance had begun seven hundred years earlier, when the monks of St.Augustine’s Abbey confused it with the manuscripts which St. Augustine himself had brought from Rome. Accordingly, the book was kept in a special shrine on the high altar of the abbey as a relic of St. Augustine. The book spent much of its medieval life in St. Augustine’s Abbey, Canterbury, until it was removed and broken up at the time of the Reformation, after which the largest, and finest surviving portion came into Parker’s possession, and thence passed to Corpus as part of his bequest of 1575. We have cared for and cherished this treasure for almost 450 years and we are delighted to share it and almost a dozen of its finest Parker manuscript companions with you over the coming months – to do so is our pleasure, our privilege and our responsibility. Parker himself would surely have approved.